Monday, January 12, we will meet in person.

Go to calendar for our schedule

Address for OHMC meditation space:

3812 Northampton St. NW, Washington DC 20015

Please arrive a few minutes early so we can invite the bell on time. You may also arrive 15 minutes early to practice working meditation by helping us set up cushions.

Dear friends,

This week, we will meet Monday evening, January 12, from 7-8:30PM ET in person at our meditation space (3812 Northampton Street NW); Wednesday morning, January 14, from 7-8AM ET online; and Friday, January 16, 12-1PM ET online/in person (Hybrid).

Magda will facilitate on Monday evening. Magda share:

During this season, when we have just celebrated Christmas and Hanukkah, and honored the continuation days of Thich Nhất Hạnh and Martin Luther King, Jr., I would like to recognize and honor the children who have done nothing to deserve the dehumanizing treatment they continue to endure.

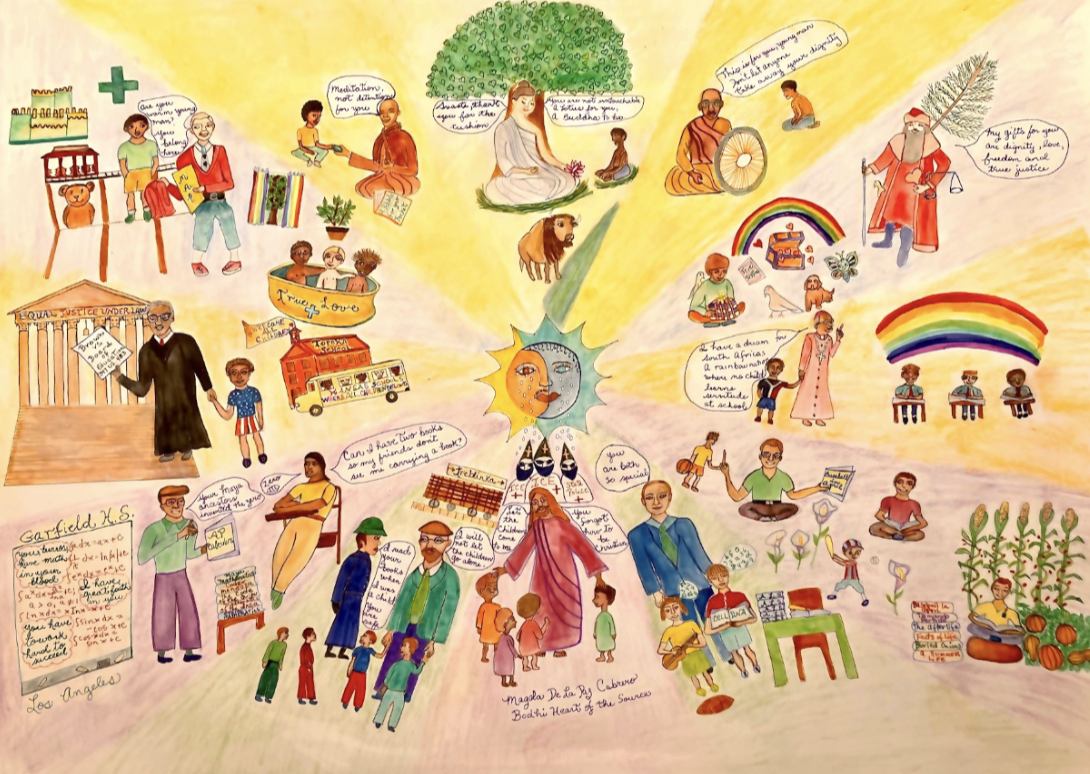

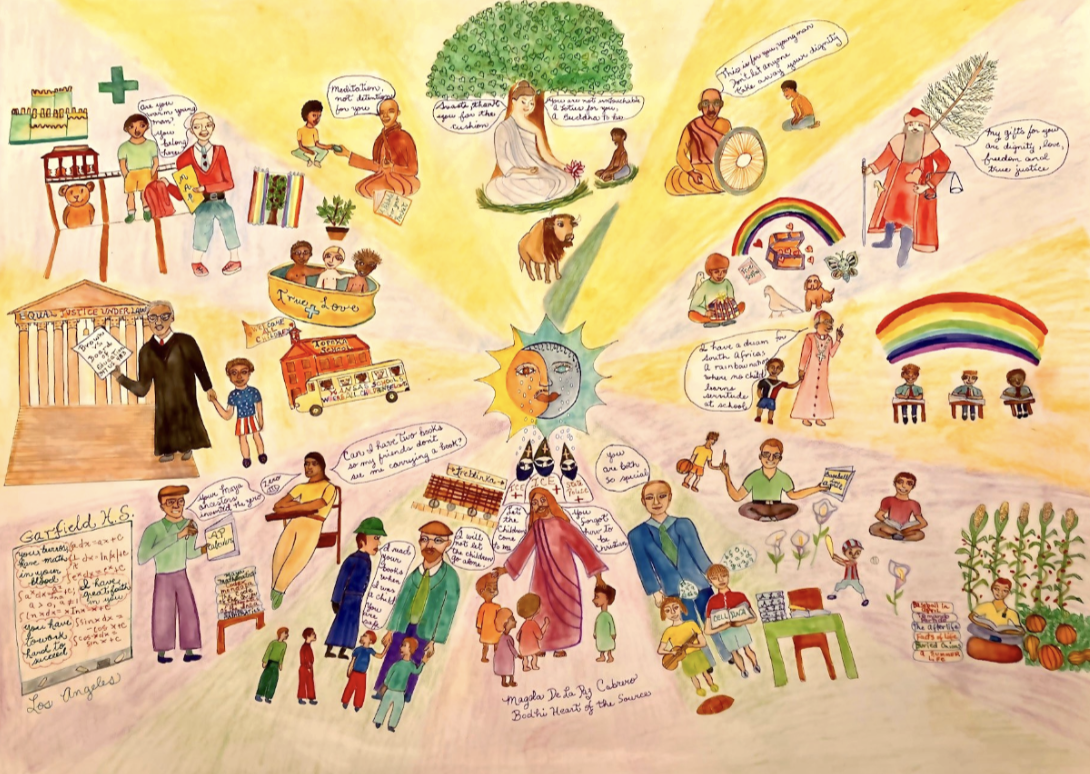

Please read more about the people, symbols, and meaning in this image.

Under the new administration, my recurring nightmare has been children returning home from school to find a parent deported. The home, meant to offer safety, becomes a site of loss. I encountered this suffering in the case of Kilmar Abrego García, supported by CASA, an organization I aided. His sudden deportation left his wife raising two young children—one with autism, one with epilepsy. The story haunts me, reflecting a cruelty hidden behind political rhetoric: children absorbing trauma they did nothing to cause.

I also recall a principal who once asked, “Do Latinx parents care about their children?” Her question revealed deep prejudice, later paired with punitive action against me in response to my writing letters to an incarcerated student. That young man, now 32, sent me a letter of gratitude and pride in what he’s built, defying the principal’s prediction. Other moments I witnessed, like the demeaning of a Latina girl or undermining a legal-rights program for immigrant students, exposed how authority, when entwined with bias, devastates children.

My work with the incarcerated student shaped my focus on restorative justice and the school-to-prison pipeline. I learned misbehavior is often a language of pain. Another time, I witnessed African American boys dropping trash in defiance at a metro station—not to express disrespect, but a statement of systemic neglect. Generations of redlining, segregation, and territorial injustice continue to affect children “whose skin resembles the color of the earth.”

This is part of a long American history. Manifest Destiny, the Mexican-American War, and subsequent racialized schooling excluded Mexican-American children. African American children faced similar barriers post-slavery, documented in the show Dr. Quinn, Medicine Woman and Wilma King’s historical text African American Childhoods. Stories of Melba Pattillo and the Birmingham Children’s Crusade show the extraordinary courage of children resisting injustice through disciplined, nonviolent action.

Amid this suffering, Thích Nhất Hạnh’s teachings offer hope. He honored children as embodiments of mindfulness, deserving of gentle guidance and love. Children nurtured in care grow roots that extend compassion; those deprived risk hardening in pain. His practices—giving pebbles for mindfulness, listening deeply—model how schools might replace punishment with presence and healing. Imagine if resources spent on detention were redirected toward love, restoration, and growth. A world in which every child carries a pebble of steadiness could prevent immeasurable suffering.

My Illustrations

One of the most important ways I engage with the world, as Thích Nhất Hạnh invites us to do, is through my illustrations. They often emerge from my own suffering in response to injustice—particularly the injustices that take place in the continental United States, where I live, and in Puerto Rico, where I grew up and where I spend a great deal of time caring for my elderly mother. I understand that injustice exists everywhere, but in this country alone there is more than enough suffering to inspire a lifetime of illustrations.

In my first illustration (at the top), I depict the sun and the moon offering equal light to boys of all backgrounds—boys who have experienced discrimination. They are surrounded by male figures who inspire, protect, and speak words of encouragement, especially to those most affected by the school-to-prison pipeline. These figures offer the boys precious gifts of dignity, wisdom, and hope.

Thầy stands among them with his book A Pebble for Your Pocket open, offering a pebble to a boy whose skin is the color of the earth and saying, “Meditation, not detention, for you.” Above him stands the Buddha with Svasti, the untouchable boy, offering him a lotus flower. On the other side is Gandhi, presenting the spinning wheel or charkha to an Indian child.

Next to Thầy is Mr. Rogers, who welcomes a child whose skin is the color of the earth into his neighborhood, offering him a map and a red sweater that mirrors his own. Nearby are boys of mixed races playing together in a pool, a reminder of the moment when Mr. Rogers washed the feet of a Black man, their feet resting side by side in the water. On the other side is St. Nicholas, offering gifts of love, freedom, compassion, and true justice to a young boy.

Below St. Nicholas stands Bishop Desmond Tutu in South Africa, dreaming of schools that do not teach servitude to the darker segment of the population, while holding the hand of a child wearing the national flag. In parallel stands Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall, whose work on Brown v. Board of Education transformed American education. He holds the hand of a child wearing the American flag. Behind them, the school in Topeka, Kansas, welcomes all children, and a bus sign reads: “Kansas schools where all children belong.”

Below this scene is Jaime Escalante, empowering young Latinx students through mathematics. On the other side is writer Gary Soto, who wrote many stories reflecting the Latino experience. The son of a farmworker, he is shown sitting in a milpa, reading—a favorite pastime from his youth.

Beneath them is my father, speaking tenderly to my two precious boys, my eldest, Andrew, and my youngest, Zachary, telling them how special they are. On the other side stands Janusz Korczak, the Polish Jewish educator who was offered safety when the “blue police officer” recognized him as the beloved author of his childhood books. He refused to abandon the 192 children from his orphanage and chose instead to accompany them when they were deported from the Warsaw Ghetto to Treblinka in 1942.

On the other side of the Buddha stands Jesus Christ, himself depicted as the color of the earth. Behind him are masked ICE agents. Jesus calls on them to stop harming children and questioning their Christianity, while the tears of the sun and the moon flow down over the agents’ faces.

In my second illustration (above), I depict a sanctuary for children in Baltimore—a metaphorical garden of territorial justice. It is a place where every child is healthy, cherished, and free to thrive. This garden embodies the visions of my teachers: Dr. King’s Beloved Community and Thầy’s teaching of Interbeing.

In my third illustration (above,) I portray the son of an incarcerated mother, like the ones that our sangha’s Engaged Mindfulness Circle supports. She stands behind bars. The boy embraces Thầy, who gently places his hand on the child’s head—a gesture of protection and a vow to witness him growing into a man of integrity.

Questions for Reflection

How can I contribute to the wellbeing of the children in my family, my community, and my society?

How can my sangha work together to meet the needs of underprivileged or unseen children?

How can I remember, cultivate, and embody the innate qualities of children to deepen my own Mindfulness?

Do I have a deep understanding of the need to nurture and care for children? How can I strengthen it?

What do I do—or long to do—to support the wellbeing of children around me and in society as a whole?