Monday, August 25, we will meet in person.

Go to calendar for our schedule

Address for OHMC meditation space:

3812 Northampton St. NW, Washington DC 20015

Please arrive a few minutes early so we can invite the bell on time. You may also arrive 15 minutes early to practice working meditation by helping us set up cushions.

Dear friends,

This week, we will meet Monday evening, August 25, from 7-8:30PM EDT in person at our meditation space (3812 Northampton Street NW); Wednesday morning, August 27, from 7-8AM EDT online; and Friday, August 29, from 12-1PM EDT in person / online (hybrid).

On Monday, Magda will guide us in exploring the theme of freedom as it appears in The Art of Power, Appendix B: Work and Pleasure—The Example of Patagonia. She will also share how she experienced freedom while retracing Thích Nhất Hạnh’s steps during her pilgrimage through Vietnam, undertaken in commemoration of Thầy’s Ashes Ceremony.

In an appendix to The Art of Power, Thầy reflects on the company Patagonia and the spirit that guides its work. Its leaders and employees walk an unconventional path, refusing the suffocating norms that weigh down so many businesses. Their purpose flows from a deeper source, not from attachment or greed. They bring the light of mindfulness into their daily work, knowing that work itself—and all the restless busyness it can invite—is not the whole of life. Their workplace becomes a space for living an examined life, one that nourishes a quiet freedom. Rather than chasing after results, they choose to walk each step mindfully and ethically. In this way, they show that true rewards still come—yet these are rewards of a different kind, wholesome, sustaining, and in harmony with the heart.

This is the kind of freedom Thầy brought to his own practice, and to ours through his example. He reminded us that we do not need to be perfect, only committed to walking the path of liberation with sincerity and joy.

In My Master’s Robe, he explains that he chose the monastic path not to escape from society, but to attain “liberation and awakening.”

“We feel free, at peace, and happy living in a peaceful environment such as this […] we enjoy hearing the sound of the bell, and it makes us feel more peaceful and concentrated each time we hear it […]” p. 63

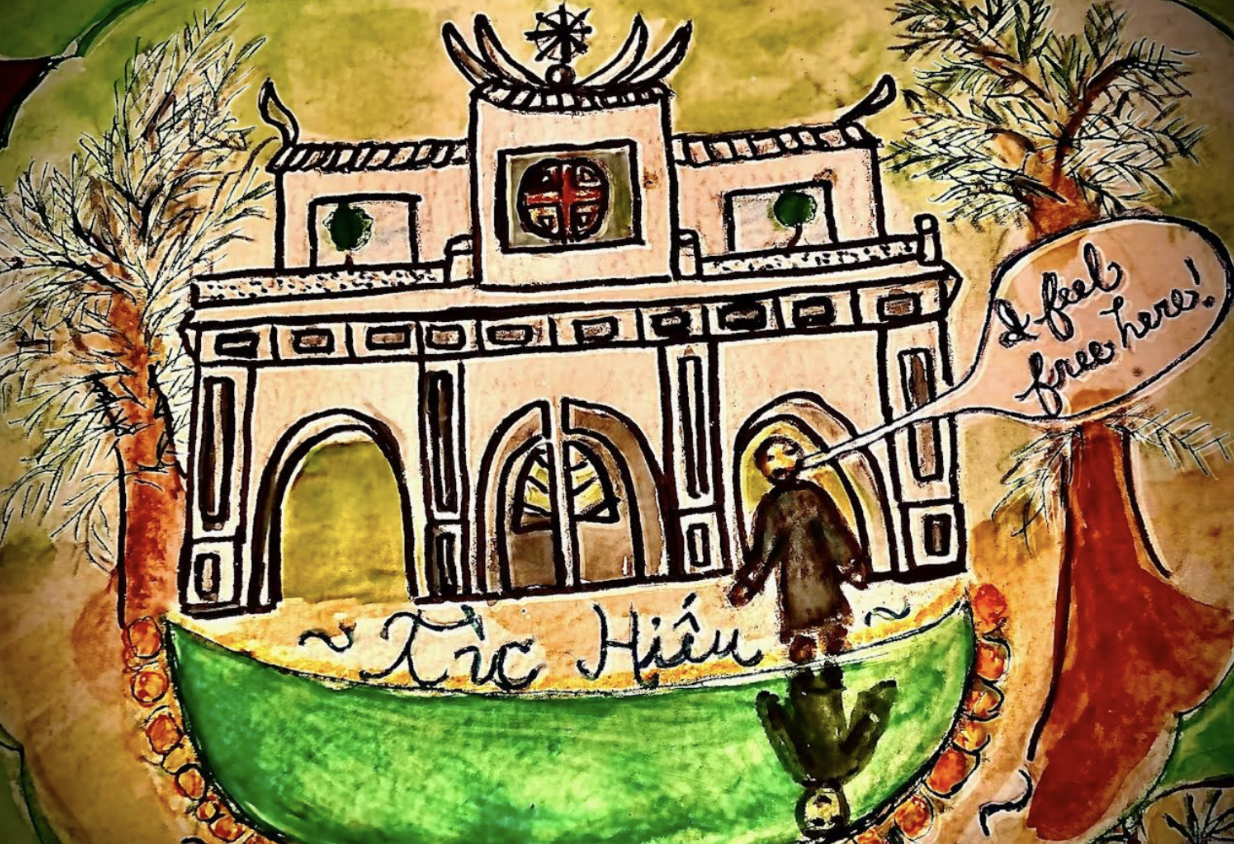

He led by example. He vowed to help all beings—words he inscribed on a column at Tu Hiếu, as I mentioned in last week’s write-up—and lived out this vow through a life dedicated to mindfulness, sustainability, and ethical living. Plum Village—and his other monasteries throughout the world—stand as some of the most powerful expressions of this model: living, breathing sanghas that manifest freedom through simplicity, integrity, and care.

What does it mean to be free?

During our visit to Thầy’s ancestral land, Sister Định Nghiêm shared how Thầy recognized her potential and empowered her to become a Dharma teacher. Her stories—infused with warmth and humor—revealed not only his greatness but also his deep humanity. At the Root Temple, we sang: “I have arrived, I am home.” In that moment, home was not a particular spot—it was a field of liberation.

During one of the ceremonies at Tu Hiếu, Abbot Pháp Hữu recalled a moment from his youth when he struggled to keep up with Thầy as they moved through a crowd. Overwhelmed, he was startled when Thầy turned, gently took hold of his collar, and said, “Don’t treat me as someone special. You and I are the same.” Those words held a lifetime of teaching: humility as the gateway to true freedom.

Thầy longed for liberation from dogma and rigidity. At Phương Bối, the first monastery he founded, he found a place to let go of convention. “We ran and yelled to shatter social restraints,” he writes in Fragrant Palm Leaves. That spirit stayed with me as I stood on those same hills, imagining him barefoot and joyful.

Thầy’s rebellion was gentle but unwavering. He did not oppose war with weapons, but with mindful breathing and courageous speech. In his very early book, written about the Vietnam war, Lotus in a Sea of Fire, he denounces ideologies that reduce human beings to tools. He saw how peasants, simply trying to survive, were crushed by those who claimed to speak for them. In response, he offered deep listening, trust, and love.

Like a raft, the Dharma must be released once the river is crossed. Thầy’s teachings reflect this truth: non-attachment to ideology, non-sectarianism, and ethics grounded in understanding rather than in rigid rules. He weaved together Theravāda, Mahāyāna, Zen, and even Christian traditions, not to dilute Buddhism, but to reveal its universal essence.

Freedom, for Thầy, also meant liberation from anger. Even in exile, even amid the suffering of war, he taught his followers to cradle their anger like a crying baby. He showed how to transform rage into compassion, and resentment into insight. In his final letter in Fragrant Palm Leaves, he wrote, “If someday you receive news that I have died because of someone’s cruel actions, know that I died with my heart at peace.” He chose forgiveness over hatred, presence over vengeance.

He also taught liberation from social conditioning, the inherited scripts that shape who we think we should be. Mindfulness, he said, is the lamp that reveals these patterns, allowing us to choose authenticity over conformity.

Thầy’s humility was not abstract, but embodied. In My Master’s Robe, he honors a tattered garment passed down from his teacher—not for its beauty, but for the lineage of simplicity it carried. He valued cooks, bell ringers, farmers. His School of Youth for Social Service offered not lofty doctrines, but love made practical, lived and shared.

Even near death, Thầy asked not to have a stupa built for him. Yet his life itself was like a stupa—a living pillar of the Dharma. At the One-Pillar Pagoda in Hanoi, I thought of him: that delicate structure rising from a single stone, lotus-like—weightless, yet grounded. Just like Thầy.

He lived as he taught: in silence, in service, in deep interbeing. He challenged power with compassion and selflessness. He gave us not commandments, but practices we are free to follow only if we want to.

True power, he showed us, is found not in control but in freedom; not in accumulation, but release; not in dominance, but humility. And in the end, that humility is the deepest liberation.